- Home

- W. Lee Warren

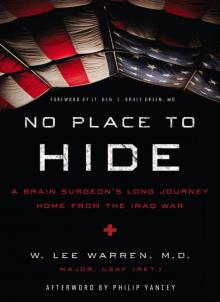

No Place to Hide Page 6

No Place to Hide Read online

Page 6

Pete was already there, and I ran to the helipad with him and several other doctors and medics. Two choppers landed at the same time, and we helped medics offload six Iraqi National Guardsmen, all obviously burned and bleeding. All of them had bloody bandages on their heads. I remembered the tour Pete had given of our instrument room. I knew we didn’t have enough sterile instruments to take care of these men quickly if they all needed brain surgery. Not to mention that there were six of them and only two neurosurgeons.

“What happened?” I yelled over the noise.

“Truck bomb. Twenty INGs were killed at the scene. These are the worst injured of the survivors. More are coming by ground,” the pilot answered.

We pushed the gurneys into the ER, where several techs, nurses, and doctors were waiting. A colonel was in charge of the triage. He was called the Trauma Czar, and his job was to organize the process of deciding which patients needed the most urgent care during a mass casualty situation. I hadn’t met him before, because he was only needed when more than one or two patients arrived at once.

The Czar moved from bed to bed, listening to reports about each patient’s vital signs and extent of injuries. A nurse went around the room marking the men’s chests or foreheads with their numbers.

I removed the bandage from my patient’s head. He had a jagged laceration that was bleeding heavily. I pulled on a glove and felt inside the cut. My finger found a big hole in the skull and some type of metal in his brain. He needed surgery.

While I was probing the head wound, a heart surgeon took packing out of a gaping hole in the man’s chest. The nurse came over and labeled him 1912. An orthopedic surgeon pulled a bloody blanket off and let out a stream of expletives. I looked down to see that both of 1912’s legs were missing. One was gone above the knee; muscle and bone protruded from the stump, and blood sprayed from his still-open femoral artery. The other leg was gone about midway down the calf, but someone had tied a belt around it so it was not bleeding. There was one shoe in the bed with him, and it contained his left foot.

The Trauma Czar stepped to our table. “What’s the story here?” he asked.

I was about to say what I’d found when the heart surgeon, who now had his gloved hand deep in the chest wound, spoke up. “He’s cooked. There’s a big hole in his heart, and he’s bleeding out. I don’t think we can save him.”

The Czar looked at the orthopedist. He looked down at the young man’s legs, then shook his head slowly.

“Major?” the Czar asked me. I reached down and opened the man’s eyes, deeply recessed and darker than his brown skin.

“Pupils are blown, sir,” I said.

“All right, let him go. Ted, Major, they need you at bed five anyway.” He walked away, and as I watched I noticed Pete pushing his patient down the hall toward surgery. It dawned on me that the Czar had referred to me only by my rank. I was not one of his people.

On the way to bed five, I passed a man in bed four closely enough to smell his severely burned arm. All of his fingernails were missing. He was awake; we made eye contact. He had a pleading look, as if he were asking me to take the pain away. I kept walking.

The patient in bed five was young, probably nineteen or twenty, blown up by terrorists because he’d been brave enough to try to help his country by joining the Iraqi National Guard. His chest was labeled 1915.

One glance and I knew I would be taking him to surgery. His head dressing had fallen off, revealing that he had essentially been scalped by the blast. Most of his forehead was gone, and I could see brain oozing from the cracks in his skull. His neck and face were burned, and his left leg was bent so that his foot was folded forward onto his calf. He had dozens of shrapnel wounds.

An anesthetist was trying to insert a breathing tube. “There’s too much blood in his airway. He’s going to need a trach soon,” he said, while using a sucker to clear the throat.

Ted the orthopedist tied tourniquets around the man’s legs, then looked up at me. “That will hold him for a minute.”

“Let’s get him to CT scan,” I said, still surprised when the techs began rolling 1915 down the hall at my command.

Four minutes later I was staring at the screen in the CT control room, watching the scan come across. “He’s got a hematoma in his temporal lobe. He’s got to go to surgery now.”

“And that’s not even the worst of it,” I heard someone say.

I turned around. The ENT surgeon, a colonel named Joe, was right behind me. “He’s also got half his blood volume in the bed with him and a hole in his trachea, not to mention the nightmare Ted’s going to have to deal with. Let’s go.”

He walked out of CT, leaving me to help the techs get the patient out of the scanner. After we moved him to the stretcher, I saw a fist-sized glob of brain tissue on the Army-green blanket where he had been. Three minutes later we were in the OR.

“Ten blade,” I said.

The scrub tech handed me a scalpel.

I stood at the head of the surgery table while Joe the ENT surgeon tried to perform a tracheostomy, a procedure to cut a hole in the trachea to use when the throat is injured and no air can get to the lungs. Ted the orthopedist and his assistant were working frantically to stop bleeding from shrapnel wounds and to amputate the man’s left leg.

I could see the man’s skull through twenty or so different scalp lacerations, each of them bleeding profusely. For the first time in my career, I did not know what to do. It was obvious that treating the brain injury would be useless if the patient died from blood loss while I did so. Every second I allowed his brain to swell, however, was costing him neurons; the already slim possibility that he would recover useful brain function was slipping away. I set down the scalpel, as the scalp was so open I didn’t really need the knife anyway.

“Raineys.”

The tech handed me a series of plastic scalp clips. Each one, when applied, can stop a quarter-inch-long strip of scalp from bleeding. I began placing them on every bleeding point. I used them all and sent for more.

Before that day, I had never lost a patient in the operating room, something I often bragged about to patients and colleagues. You do not get to die in my OR, plain and simple. If your disease or injury has mandated that this is your day to go, then do it in the ICU or before you get to the hospital. But if you make it to my surgery suite, you’re going to survive at least long enough to die in the recovery room. I’m in charge, and you’re not going to mess up my perfect record.

All those thoughts went through my head — along with the unwelcome realization that the rules were different here, that this patient had a different playbook, and that he’s not listening to me. I thought, Maybe I’m not in control here.

Joe managed to get the trach in, then he tried to stop the bleeding from the man’s jugular vein, carotid artery, broken mandible, crushed nose, and tongue lacerations.

Ted was fighting a losing battle also. The patient’s pupils were dilating, meaning the brain swelling was worsening. We were running out of time. The anesthesiologist told us he had given the patient all of the available blood of his type, and the universal blood type, O negative, was very scarce. He said there were twenty US Marines en route to the hospital after a firefight, and some of them would probably need blood as well.

The anesthesiologist reached past me and squeezed a liter bag of saline with both hands, trying to improve the blood pressure. He looked over my shoulder and said to all of us, “Do you want me to give him the O neg?”

We looked at each other but no one spoke. There was no surgeon’s bravado, just three men considering something we knew we wouldn’t have to do back home. American hospitals rarely lose someone to blood loss, because we have more than enough of most any supply we need. Even if we run out of something, other hospitals can usually provide it quickly. Every patient gets whatever blood quantities they need, and we never give up on someone easily. In war, it’s different. We knew that if we gave this patient the blood, then someone else, possi

bly an American, could die for lack of it. And our patient, even though a couple of hours ago he’d been young and strong, was unlikely to recover from these injuries no matter how much blood we gave him.

I knew what I had to do. I might have been the new guy, but I was at the head of the table. “That’s it. Everybody stop. No more blood product.”

Ted looked into my eyes and nodded slowly. Joe’s face fell and he walked away from the table, snapping off his surgical gloves as he left the room.

I felt warmth on my right leg. I looked down — somehow my surgical gown had folded onto itself, and my leg was exposed. I was soaked in the man’s blood. Even my sock and shoe were red, wet, and sticky.

My left glove was rolled down a little, and his blood had crept under the edge and onto my skin. His pulsating arteries had hit all three of us in the face and neck; we were all covered in the blood this Iraqi National Guardsman had shed as a result of a terrorist’s hateful bomb. Trying to help his nation rise from tyranny into democracy, this man had bled to death.

The anesthesiologist spoke again. “He’s gone. No pulse.”

I looked up at the clock on the wall and replied, “Mark the time. 1915 is dead.”

Ted looked at me and said, “Nice try.”

I had no more words. We don’t quit in America — not for lack of resources, not for lack of blood. We keep going, we win, we save lives. This was unacceptable, unprecedented, outrageous.

The floor was now totally red. So were the walls of the tent to my left; everybody’s scrubs, every bit of formerly white sponge I could see, were now red, along with all the instruments and drapes.

To my right, three feet away, two general surgeons were operating on another patient, also bleeding everywhere. I was shocked that in my efforts to save my patient, I hadn’t noticed them before this. Their patient survived the day only to die of shock and blood loss the next morning.

I walked into the surgeons’ locker room, removed my blood-soaked scrubs, and sat on a bench to catch my breath. I was defeated, but the day was just getting started. More patients were coming in. My confidence was shattered, and doubt crawled up my spine into my brain and expanded like a gas until I was convinced I would be unable to survive here.

I changed into clean scrubs, but I didn’t have another pair of socks, nor time to walk back to my trailer. I washed my socks in the sink, watching the red turn to pink and ultimately a not-quite-white again. I walked back into the ER, squishing a bit in my shoes, nauseated, scared, wishing the world wasn’t red anymore.

CHAPTER 6

I’M NOT THE ONLY ONE GETTING SHOT AT HERE

By late afternoon on my bloody first Sunday in Iraq, I was emotionally spent, physically exhausted, and professionally vexed. I was allowed a fifteen-minute “morale call” home. After connecting through a switchboard operator in Bahrain, I waited five minutes on the line for another operator in San Antonio, who then connected me to the only number I had to reach my children, their mother’s cell phone.

The call went to voicemail.

Dual feelings washed over me: a longing to hear my kids’ voices and anger over the call not being answered. I swallowed my emotions and tried to sound normal after the beep.

I left a message: Daddy was safe and missed and loved them. I asked them to write. I hung up and dialed the operator again, hoping to call my parents instead. The operator said I’d already used my morale call for the week.

I hadn’t spoken to my kids since Christmas Day, eight days before.

That evening, Pete invited me to church. We walked across the base to a tent with a brown wooden steeple in front. Surrounded by sandbags to protect against a mortar or rocket attack, it looked nothing like a church. A line of soldiers waited to enter.

The man in front of me carried a squad automatic weapon, known as a SAW. His partner bore an M – 16 with an attached grenade launcher. I saw a young man carrying a camouflage Bible, and I wondered, In what scenario would you need your Bible to be camouflaged?

The doors opened, and the Catholics began to exit from their service, which had just ended. A priest in brown DCUs but wearing a bright green robe blessed the exiting parishioners, who leaned forward to receive his encouraging words as they shouldered their weapons. Our line began to move.

Pete and I sat on folding chairs on the second row. A Marine lance corporal sat next to me. He didn’t remove his armor or lay down his weapon. He stared at the cross on the wall and sat silently while the small band on the stage began to sing “Amazing Grace.”

The service included quiet time for prayer and reflection. A few people walked to the front of the room, where they were met by chaplains to talk privately or pray together. Partway through the service, the lance corporal placed his rifle on the floor and released the strap on his body armor, allowing it to hang open like a man loosening his tie after a long day at the office. A very tall Army soldier in front of me was on one knee in prayer, and I noticed him sobbing into his hand.

I placed my hand on the kneeling man’s shoulder. Without turning around, he took my hand, squeezing it into his giant palm.

As the prayer time continued, music softly playing in the background, I felt as if a weight were driving me into my chair. The day’s events came to mind suddenly — not in a stream, but all at once. I felt the futility of watching someone die for lack of blood, heard the screams of burned men, heard the call go to voicemail, remembered I was here. Elbows on knees, I cradled my face in my hands and argued with God.

Why, God? Why am I here? Why are all these things happening? Why did my brother get sick, my grandfather die? Why did my marriage fail? Why couldn’t I save that kid? What will happen to my kids if I die over here? Why are you doing this to me?

I was not crying; I was angry. Angry that my whole life seemed to parallel this mortar attack, even long before I arrived in Iraq. I wanted to know why, but instead of answers I heard explosions.

As the pastor was beginning to deliver his message, a powerful explosion drowned out his words. The subsonic thud caused by the mortar’s detonation punched my chest and popped my ears. Everyone dropped to the floor, clutching at our body armor as an even louder second explosion shook the chapel.

The Alarm Red siren began to wail.

“Everyone stay here,” the chaplain said. “There are no bunkers close by, so we might as well just pray.”

He prayed for our safety, and for everyone on the base, everyone outside the wire, and for the souls of the men who were shooting at us. I remembered Jesus’ words, Love your enemies, but I didn’t much feel like praying for them at the moment.

I am not the type to say something like, “God sent those mortars to shake me up, get my attention.” I believe God has more important things to do than putting thirty-five thousand people in harm’s way to make a point to me. I’m comfortable blaming the attack on Muslim extremists who wanted to kill all of us, and to whom I was nothing more than a generic enemy. Nevertheless, in that moment the attack felt very personal, and my reaction to it still surprises me.

I looked around the room. A few chairs to my left sat an Army Ranger with a square head and narrow eyes. He had grenades in a pouch on his chest, and his huge hairy hands wrapped tightly around some type of automatic weapon. He stared straight ahead, but I noticed a thin bead of sweat running down the right side of his face. It wasn’t hot in the chapel.

Two teenaged Marine privates in gym shorts and T-shirts sat behind me. The girl had a peaceful look, her eyes closed, her lips moving silently in prayer. The boy had more pimples than any three average middle school kids, an M – 16 at his feet, and a Bible in his lap. He hugged himself tightly and was rocking back and forth, staring at the ceiling.

Machine-gun fire answered the mortar attack. Another mortar exploded. In the silence after the mortar, I heard my dog tags rattle and remembered that my blood type was printed on them. I wondered how much B positive we had left at this point in the day.

A few moments before, I ha

d been silently yelling at God, asking, Why me? But as I looked around the chapel I felt something new: I’m not the only one getting shot at here.

I was suddenly aware that every person in the room and everyone on the base had personal lives, live that were seriously affected by this deployment. Some of these people had struggling marriages, family illnesses, financial problems, or other issues that they’d been dealing with before the war and that would continue to trouble them after they returned home. Even those whose lives were in order were under the strain of separation and the peril of death. I wasn’t alone; it wasn’t all about me.

Over the next hour, there were thirteen explosions, each answered by bursts of machine-gun fire and the low thuds of our own mortars shooting back at the bad guys. Long before the attack ended, an Army major named Greg walked onto the stage, joined by a bony young lady in body armor who picked up a guitar. They sang a hymn as the chaplains asked us to take communion together.

As they passed around the trays containing unleavened bread and red wine, I felt something breaking loose inside of me, something shifting. I could not yet tell what it was, but I knew I was changing. For months, I had been focused on the events of my life that remained stubbornly out of my control, and I was angry and bitter about that lack of control. I was focused squarely on myself. Sitting in the chapel that day as mortars exploded all around me, holding broken bread and a plastic thimble of wine, I zoomed out of myself.

The attacks finally ended, the All Clear was sounded, and the service came to a close. The singer, Greg, announced that the entire church band was going home in a few days and the chapel would need new musicians. As I strapped on my helmet, I was vaguely aware of Pete disappearing up toward the stage. A moment later, he returned — with Greg. Greg had a thin smile, happy eyes, and a weary droop, like he’d been carrying a heavy load for a long time and was about to deliver it.

No Place to Hide

No Place to Hide