- Home

- W. Lee Warren

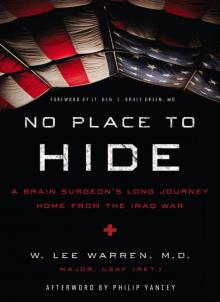

No Place to Hide Page 12

No Place to Hide Read online

Page 12

I stood in the darkness, hearing the anesthetists scrambling for their hand ventilation bags so they could keep breathing for the patients while the power was out in the operating room.

Once during my residency, when I was about to clip an aneurysm, someone in the room tripped over the extension cord to the operating microscope and unplugged it. The scope went black, with my hands deep inside a girl’s brain. Dr. Wilberger very calmly said, “Lee, hold your hands perfectly still, no matter what. If you move you’ll either tear the aneurysm and kill her, or rip her optic nerves and blind her. This is what brain surgeons do —be still until you can see, and control your hands.”

I stood there that night in Balad, waiting for the generator to restore the lights in the room and trying not to make the Marine’s brain injury worse. Vic had his hands in the belly of his patient, and we both held still until we heard the roar of the machine, followed in a few seconds by the lights slowly coming back on.

I looked across the room at Vic, and he winked at me.

While he was closing his patient’s wound, a tech ran in and said, “Dr. Vic, there are four more patients with abdominal wounds in the ER. They need you stat.” Vic performed the fastest closure of an abdomen I’d ever seen.

Now, here we were five days later, and it wasn’t infected, and the patient was eating and doing well. I thought, It looks pretty good to me.

The only advantage of rounding in such a huge group and with patients who didn’t speak English was that most of the usual courtesies of rounding in America were absent; we didn’t spend much time on the “And how are you today, Mrs. Johnson?” social interactions, at least when it came to the non-Americans. As we neared the end of the fourth hour of our first day rounding with all the veterans gone, I was close to finally having all of my new colleagues’ names down, and to honing in on their personalities.

My new partner, Tim, had arrived the day before, smelling of the coffeehouses of Al Udeid and sporting a tan from a few days by the pool there while the war machine tried to find him a ride downrange, where I’d been waiting for him. Tim was about my size but had a dark complexion, dark hair, and dark eyes, almost like a negative of Pete. He’d had the same overwhelmed look I’d had when I gave him the tour, that look that said, “Wait — I’m supposed to be able to do what with all of this old equipment?”

This morning we were slogging through the last of the patients in the long-term care ward, and I’d heard just about every one of our new surgeons flex his philosophical muscles, each one crashing into the same ideological walls and ceilings I’d hit a few weeks before regarding just about all of the treatment decisions the now-departed other surgeons had made, since the new guys had yet to fully taste the realities of this environment.

We came to the bedside of a Syrian Al Qaeda terrorist whose right arm wounds were packed with gauze. He had been injured while trying to set off a car bomb, and later that day he would make his third trip to the operating room.

“I’ve never seen extremity wounds managed like this,” said one young orthopedist through a nasally New England accent. “It’s prehistoric. This guy’s going to lose that arm.”

A sniffing sound came from his partner, an Australian named Geoff. He had reading glasses on a chain around his neck, his head was polished marble bald, and he looked old enough to be the other guy’s father.

“Look, mate, that’s how it’s done in a dirty environment. You’re too young to have seen this work before. He’ll be wiring bombs again in no time, if he ever gets out of Abu Ghraib.”

“Well, it’s unacceptable. That’s not how it’s going to be done here.”

I hid a little smile, remembering similar statements most of the other surgeons had made that morning during rounds, including an almost verbatim reiteration of my original argument with Pete about how we managed head-injured patients. Except that today I had played the role of Pete, and Tim had played the naive and untested me.

We’ll see about that, I thought.

Several beepers rang at once, a group mass-casualty page. Here’s where we would see what these guys had in them.

We ran into the emergency department and saw Army medics and the new ER staff wheeling in ten stretchers filled with screaming, bleeding men. Colonel H erased any doubts I had about his ability to function as both administrator and surgeon. He ran up to one of the medics. “What happened, Specialist?”

“Ambush near Mosul, sir. Six Americans and four Iraqi policemen survived for us to pick up. Everybody else is dead on the ground. We got multiple gunshot wounds.”

Colonel H pointed at one of the older general surgeons, a bald-headed colonel named Dave.

“Dave, you’re the new Trauma Czar. Everybody, figure out what’s going on with these patients and triage them. Nobody second-guesses Dave. Let’s get to work.”

Chris already had his hands on a young corporal’s bleeding abdomen. Geoff and Bill, the orthopedists, started putting tourniquets on bloody limbs. The ophthalmologist, Augie, ran around the room shining a light into patients’ eyes. Another general surgeon, Brian, took over CPR on an Iraqi man who was already in cardiac arrest.

One of the Iraqis had a bullet hole in the middle of his forehead, and I let Tim examine him while I watched. The man was maybe twenty-five, wore a wedding ring, and his lighter-than-normal complexion and clear green eyes made me think he had some European blood in his family line.

Tim performed a solid neurological exam, then looked up at me with his jaw clenched. He blinked hard, and I noticed a tiny tear on one of his eyelashes. “Brain dead,” he said.

I repeated the exam. No pupillary response. No reaction to painful stimuli, no reflexes, his body temperature was normal, and he’d been given no medications to confuse the exam.

A nurse wrote 2037 across the man’s chest while I double-checked Tim’s findings.

Dave, the new Czar, appeared at 2037’s bedside. Already his forehead was covered with sweat and he looked nauseated. But when he spoke, I knew he was fine. “Okay, you guys. A bunch of the other patients are going to need the CT scanner. What’s your situation?”

I looked at Tim, his eyes now bloodshot with the rage you feel when you’re too late to save someone. “Your call,” I said.

Tim looked at Dave and shook his head. “He’s brain dead, sir.”

Dave sighed. “Then call it. As soon as you know you can’t save a patient, move on to somebody else. If you’re standing around a corpse, you’re wasting someone else’s chance to survive. Call it.” He turned and walked off.

Tim looked at me, his eyes red and wide and no longer full of fear. He turned to the nurse. “2037 is DOA, mark the time as eleven twenty-three.”

I spent the next couple of hours watching the new vascular surgeon, Todd, attempt to save the leg of an American. A lot of surgeons would have simply amputated the man’s leg after seeing the mangled arteries and veins. Todd delicately picked out the bullet fragments, gently identified the ends of several blood vessels, and sewed in Gore-Tex patch grafts with hundreds of tiny sutures. His hands were steady, his focus laser-like, and he worked with a grace and efficiency I’d seen in only a handful of other surgeons in my career.

When Todd placed the last stitch, he took the clamps off the patient’s arteries. I watched as the man’s foot turned from a livid blue to a pinkish red. Todd reached for the foot, held his hand there for a moment, and casually said to no one in particular, “Good pulses. I think he’ll keep his leg.”

As I went from bed to bed that evening on rounds, I heard the stories of the patients and procedures involved in the day’s work. Each of the surgeons had lost their mass-casualty virginity in different ways, but other than 2037, who died before he arrived, there were no deaths in our hospital that day. To a man, the surgeons’ eyes were transformed from their clear idealism into the bloodshot realism of men who’d been measured and had passed the test.

We were going to be okay.

That night, Tim came over to my place and we chatted fo

r a while, getting to know each other. I wondered how we would operate together, but I felt somewhat reassured by the training and sensitivity he’d shown at the Iraqi policeman’s death.

There was a knock at the door, and I opened it to find three men, all captains, in DCUs.

“I’m Joel, this is Jeremiah and John,” the tallest said. “Jeremiah and I replaced Brian. We’re physical therapists. John is an occupational therapist. Brian said you guys watched movies here at night.”

They came in, and John handed over a sack full of potato chips and dip. Movie night was still on, apparently.

We watched an old Steve Martin movie, The Man with Two Brains, which was hysterically funny to us because it’s about a brain surgeon. Every time he’s in surgery, a stray cat runs through the operating room and the surgeon yells, “Somebody get that cat outta here!”

When that movie finished, Joel mentioned that his wife had sent him the World War II miniseries Band of Brothers. We watched the first episode, and a vague heaviness settled over all of us. Watching a story about young men in another time and place go through the fight together, I wondered what the next episode of our own war would hold.

The next morning before rounds, Tim and I took Adnan/1255 to the operating room to repair his head and cure his case of skull belly. We’d decided the night before that since the infection rate in the hospital was so low since the Air Force had taken over, we would start putting the bone flaps back in earlier. Adnan would be the first patient to undergo the skull repair, called a cranioplasty, in the tent hospital environment.

It turned out that Tim and I were both left-handed, so we could work side by side and not bump elbows. Tim was efficient and had steady hands, but he didn’t say much as we screwed the bone back onto Adnan’s head with tiny titanium plates. I missed the easy rapport Pete and I had had, and wondered whether surgery with Tim would always be so remote and formal.

I remembered, though, that I’d been pretty nervous the first time I’d operated with Pete, wondering if I’d measure up to his standards and if I’d be accepted by the others as an equal. So I looked at Tim and said, “Hey, I like the way you operate. I think you’re going to do great here.”

Tim’s masked face hid his expression, but I saw smile lines form in the corner of his eyes. He turned toward the anesthetist and said, “Somebody get that cat outta here!”

CHAPTER 14

THE NIGHT VANIA’S FAMILY WAS SHOT

EMAIL HOME

Wednesday, January 26, 2005

Good morning, America.

I awoke this morning feeling the full force of the fact that I am 7,000 miles from home, that I left one month ago today, that I have a steep road ahead of me when I get back to America. These realities crushed me down into the mattress, as if to convince me that I should just stay in bed.

But I prayed about it, and I remembered this: God is not surprised that I am here. All the days of my life were written in his book before one of them came to be (Psalm 139:16), and God determined the exact time and place where I would be in my life (Acts 17:26). That means that I am right where I am supposed to be.

Get out of bed, Lee. You’re right where you’re supposed to be. Carry on.

Thanks for listening. Since I don’t have my normal folks here, all of you got to work through that with me. I appreciate it.

Many of you have written to ask about the baby who was shot in the head. Yesterday we learned a lot more about him, including his real name. You don’t have to pray for 2013 anymore . . .

I walked into the ICU to check on 2013, the baby I’d operated on after he was shot in the head when his parents ran a checkpoint. A young Iraqi woman stood by his bedside, looking down at him.

In another time, another place, I would have thought she was a pretty young woman. But the person by the bedside, looking into my eyes, had an edge to her, steel in her spine. She said something in Arabic, and when I shrugged my shoulders and held up my hands, she turned away. She touched 2013’s face gently and stroked his hair. Her eyes moistened, but when she looked at me again I saw not sadness but anger.

She might have been twenty, but I had learned that the rough environment and constant stress in Iraq made people look older than they really were. She wore a brown sweater over a khaki dress, had her hair pulled back in braids, and her head was not covered. I wondered if she was the baby’s mother, but we’d heard from the soldiers that his parents were both killed in the shooting that night. She kept one hand on him and put her other hand on her heart, saying something softly over him that sounded like prayer.

I asked, “What is your name?”

She turned her head slightly, and I was glad that looks couldn’t actually kill.

“Perhaps I can be helping,” Isam said as he entered the ICU. “The guards sent for me.”

I nodded. “Thanks. I need to know who she is, but she won’t talk to me.”

Isam cupped his hands in front of him and bowed slightly toward the girl. He spoke to her softly, and she replied. He pointed toward me and said something else. She wiped a tear from her eye and looked toward me again, her expression much softer now.

“Her name is Vania,” Isam said. “She is his sister. I explain you are his doctor, who save his life. She thought you were soldier.”

Vania’s anger toward me was replaced by a grim gratitude. I never saw an expression resembling happiness cross her face, but at least there was a distant, hopeful look, as if she might be starting to believe that their life could return to some semblance of whatever normal was for them. With Isam’s help, I learned that the baby’s name was Mohamed, and that his parents were not dead after all. Instead, they were being treated in one of the few remaining civilian hospitals in Iraq, and were expected to fully recover from their wounds. This happy news was surprising but not shocking, since pretty much everything we heard about events outside the wire seemed to be subject to change. Information filtered unreliably through the fog of war.

I asked Isam whether Vania knew the details of the night her family was shot. When she heard his question, she sat down on the edge of Mohamed’s bed. Her face hardened, and her eyes looked past Isam, through the tent walls, into a world where foreign armies shoot into cars full of babies and mommies and daddies.

Over the next few minutes, through interpreted words and looks that needed no translation, a tragic story emerged. As I listened, as hard as this is to say, I couldn’t find anyone to blame for what had happened.

Mohamed’s parents had been driving along late at night. In a heavy rainfall, they came upon vehicles blocking the road and American soldiers yelling in English. A car was on fire beside the road. A few bloody bodies were strewn about, and the soldiers had several men lined up against one of their trucks, pointing their guns and screaming words Vania’s father could not understand.

He did understand, though, that he and his wife and baby were in danger. He wanted only to get away, to get his family safely home. He wanted nothing of the war or the insurgency or the revolution Saddam had preached his entire lifetime. He just wanted his family to be safe.

Their world, Vania said, is one in which people are frequently ambushed, attacked, and senselessly murdered. It is a world where suicide bombers blow themselves up at weddings. Terrified, her father tried to accelerate past the burning car. That was all he remembered when he told this story to Vania days later, after the doctors had found her and brought her to her parents.

I thought about the Marines who had been there that night — probably just teens, perhaps in their twenties, trying to make sense of a chaotic and stressful situation. The part of the Sunni Triangle near Ramadi where the incident took place was at that time one of the most dangerous areas in Iraq, and we took care of Marines almost every day who had been shot or blown up because of insurgent activity there. Through the darkness and the rain, they would not have been able to see inside the car approaching them. They would have shouted at the driver to roll down the window and communicate.

The car stopped. No explosions occurred. The Marines ran closer and looked inside — finding, to their horror, not a terrorist strapped to a bomb but a family of three, bleeding and moaning. The baby had a bullet hole in his forehead. Someone called for a medevac Black Hawk, and the medics loaded the baby on board. The parents were less severely injured, and the medics were able to arrange for them to be treated locally by civilian doctors.

It was a terrible situation, the kind of tragedy war forces on people. No one was wrong. No one was right.

Vania trembled as she finished her story. I told her through Isam that Mohamed had come through his surgery well and was ready to go home. I took the stitches out of his head while she held her little brother. I asked if I could hold him one more time, and she handed him to me.

As I had done every night since operating on him, I took Mohamed in my arms and pulled him close. He was one of those babies who burrows into your arms and lays his head on your shoulder as if he’s going to melt into you. For me, the moment expanded: I felt the arms of each of my children, I felt all the love in the world flowing into me through this Iraqi baby I would never see again, and I quietly prayed a prayer of protection for him into his ear.

I had tears in my eyes when I gave Mohamed back to his big sister, a girl forced to face grown-up realities because of decisions made by two world leaders she’d never met. She said thank you to me and to the nurses and Isam, but her tone and the look in her eyes said more than her words. The uniform I wore represented the people who had put her family through this hell, and despite the fact that I had saved Mohamed’s life, Vania no doubt felt the double cut of having to be grateful to the same people who had created their problem.

No Place to Hide

No Place to Hide